Explore the creators

Showing 232 creators in the collection

232 creators

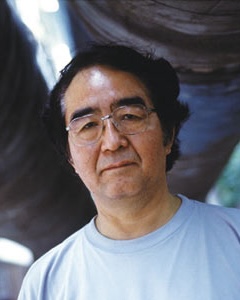

Yang Jisheng

Yang Jisheng (1940–) was born in Xishui County, Hubei Province, and is one of China’s most important independent historians, writing internationally acclaimed books on the Great Famine and the Cultural Revolution. He also served as a h senior reporter for Xinhua News Agency, a professor, and has long been engaged in political economy, history, and social commentary. His career, spanning half a century, has profoundly influenced social thought and political discourse in post-reform China.

In 1960, Yang was admitted to Tsinghua University to study tractor engineering in the Department of Power Engineering. He graduated in 1966, a time when the Cultural Revolution broke out. In 1968, Yang joined the Tianjin branch of Xinhua News Agency as a reporter. In the 1970s, he wrote articles reflecting social realities, such as <i>The Large-Scale Occupation of Civilian Housing by the Military in Tianjin Seriously Affects Civil-Military Relations and Investigation of Labor Productivity</i> in Tianjin, revealing his keen attention to China's social reforms.

Over several decades at Xinhua, Yang accumulated extensive experience in political, economic, and cultural reporting. He served in several important roles, including editorial board member and director of the Theory Department at <i>Economic Reference Daily</i>, director of the News Publishing Center, and director of the News Investigation Department. Additionally, he was the editor-in-chief of China Market magazine in Hong Kong. In 1984, Yang was named one of the first National Outstanding Journalists, and in 1992, he was awarded the State Council's Special Government Subsidy for Distinguished Experts.

After retiring, Yang continued to be active in commentary and academia, contributing to magazines such as <i>China Reform, China Entrepreneur</i>, and <i>Method</i>. In early 2003, he became the deputy editor-in-chief of <i>Yanhuang Chunqiu</i> magazine.

Yang’s academic and commentary works cover a wide range of topics, including modern Chinese politics, social change, and historical memory. One of his representative works is <i>The Political Struggles in the Era of Chinese Reform</i>, which was published in Hong Kong at the end of 2004. This book contained his firsthand interview materials from 1976, the year of Mao Zedong's death, to the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. It also includes three interviews he conducted with then-General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, who at the time was under house arrest after the 1989 protests. Because Zhao had promised not to release these interviews during his lifetime, they were only published after his death. This book provides a deep reflection on the Reform Era and reveals many of the power struggles of the time. Through his portrayal of Zhao Ziyang, Yang not only showcases the political stance of this reformist leader but also presents the intense political battles during China’s transition.

Yang came to international attention through his 2008 book <i>Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine</i>. This book meticulously records the famine, revealing the catastrophic disaster caused by Mao Zedong’s policies. Using a large number of archival materials and testimonies from survivors, Yang describes the tragic deaths of approximately 36 million Chinese people due to famine and violent policies. Although the book was banned in mainland China, it was widely distributed internationally and won several prestigious awards, including the Hayek Book Prize from the Manhattan Institute.

In addition to Tombstone, Yang’s other internationally known work is his 2016 work The World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. In this extremely long and detailed work, Yang describes the events between 1966 and 1976, also using archival material and first-person interviews.

He is also the author of <i>The Deng Xiaoping Era: A Chronicle of China's Reform and Opening-up</i>, which explains the political and economic structural changes during the reform period. This book reviews the process of China’s reform and opening-up, focusing on Deng Xiaoping’s leadership in economic reforms and political adjustments. Yang evaluates the successes of China's economic development and the challenges encountered in political system reforms.

When discussing the future direction of China's reforms, Yang stated, “Power does not belong to the majority. There is a significant difference and unfairness between those who have power and those who do not. After thirty years of reform, the "cake" has grown very large, but its distribution is highly unfair. Those with power have received a large and favorable portion, while those without power have received very little. The system formed over more than thirty years of reform and opening up is called the ‘power-market economy system.’ Although it is a market economy, it is a market economy controlled by power. Power manipulates the market economy. Under the control of power, the market is distorted and imperfect. The fundamental problem is inequality. The gap between those with power and those without has created significant conflict and disparity, leading to social disharmony. This is why the idea of ‘building a harmonious society’ and the need for stability maintenance were proposed — all due to the social disharmony and inequality caused by the system.”

Additional resource: <a href=”https://www.chinafile.com/library/nyrb-china-archive/finding-facts-about-maos-victims”>interview with Yang Jisheng by Ian Johnson</a>

Yang Xianhui

Yang Xianhui (1946—), writer. Yang was born in Lanzhou, Gansu Province. In 1965, during high school, Yang went to work in the countryside as a sent-down youth. In 1971, he was admitted to the Department of Mathematics of Gansu Normal University as a worker-peasant-soldier student. After graduation, he worked as a middle school teacher in Gansu, and later in Hebei as a party committee secretary and a communication officer at a local salt farm. In 1988 he joined the Tianjin Writers' Association to work full-time as a writer.

His historical novels such as <i>Chronicle of Jiabiangou</i> and <i>Chronicle of the Dingxi Orphanage</i> portray life during the Anti-Rightist Campaign and the Great Famine, and are constructed from interviews with a great number of survivors and recollections of his own time as a sent-down youth. The two books have drawn comparisons to Solzhenitsyn's <i>Gulag Archipelago</i>, which chronicled Soviet labor camps.

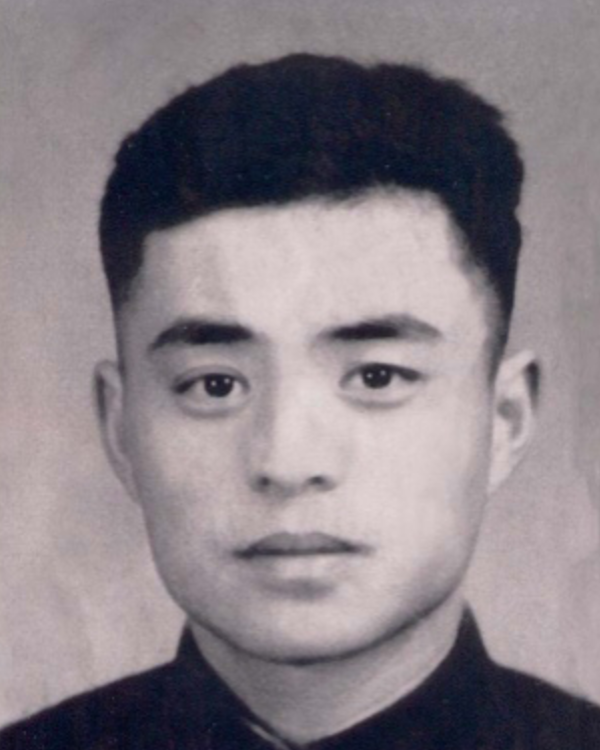

Yang Xiaokai

Yang Xiaokai (October 6, 1948 - July 7, 2004), also known as Yang Xiguang, was an economist. Yang was born in Dunhua, Jilin Province and grew up in Changsha, Hunan Province. Yang's father was a senior CCP cadre in Hunan, who was labeled a Rightist Opportunist for his support of Peng Dehuai, the defense minister, who was dismissed for pointing out the failures of the Great Leap Forward. Yang was rehabilitated in 1962. When the Cultural Revolution broke out, Yang's parents were labeled Counterrevolutionaries, and Yang, who was in high school, became a child of one of the "Five Black Categories," which formed what was essentially a permanent underclass in Mao's China (the others were landlords, rich farmers, counter-revolutionaries, and bad elements). Yang then joined the Rebel Faction of Red Guards. In 1968, Yang wrote a Dazibao (big-character poster) entitled "*Where is China Going?* ", where he criticized China's privileged bureaucratic class, and advocated the establishment of a Paris Commune-style government. As a result, Yang was detained in a detention center for more than a year, and was then sentenced to ten years' imprisonment for counterrevolutionary crimes in 1969, and was exiled to work in a labor camp in Hunan province until he was released in early 1978. Yang later wrote a book about his experiences during these ten years entitled *Captive Spirits: Prisoners of the Cultural Revolution*.

Inspired by Marx’s *Capital*, which Yang read in the detention center, he decided to become an economist and taught himself economics in prison. After his release in 1978, he was admitted to the Institute of Economics of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and received a master's degree in econometrics. In 1982, he was employed as a lecturer at Wuhan University. In 1983, the High People’s Court of Hunan Province announced that the counterrevolutionary conviction of Yang had been annulled. In the same year, Yang went to Princeton University and received his Ph.D. in economics in 1988. In 1990, Yang was appointed as a tenured professor at Monash University in Australia. In 1993, he was elected as a fellow of the Australian Academy of Social Sciences. He died on July 7, 2004, at his home in Melbourne, Australia, due to illness.

Yang's achievements in economics include the development of inframarginal economics and the new classical economics, and he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Economics twice, in 2002 and 2003.

Yao Jianfu

Yao Jianfu (October 9, 1932—) was born in Nanjing. His father was a Kuomintang officer who participated in a coup against the KMT during the Huaihai Campaign; his mother was an elementary school teacher. Yao graduated from Harbin Institute of Technology in 1957 and was assigned to the China Academy of Agricultural Mechanization Science as an engineer. During the Great Famine, Yao was sent to work in a rural commune in Shanxi Province for one year, where he witnessed firsthand the conditions of the peasants. During the Cultural Revolution, Yao's family was targeted; Yao's mother was beaten to death by Red Guards and his father hanged himself. Yao himself was labeled a counter-revolutionary for having made disrespectful remarks about Jiang Qing (the fourth wife of Mao Zedong and deputy director of the Central Cultural Revolution Group in 1966), and was sent down to a labor camp in Hunan province. He was rehabilitated after the Cultural Revolution.

In 1982, Yao was assigned to the CCP Rural Policy Research Office and the Rural Development Research Center of the State Council as a researcher; in 1992, he became a researcher at the Rural Economy Research Center of the Ministry of Agriculture, a position he held until he retired. In 2003, he was a coordinate researcher at the Yenching Institute of Harvard University.

Yao is concerned with public affairs and is a frequent commentator on history and politics in China. He has interviewed Zhao Ziyang, a reformist leader during the 80s and purged after the 1989 student movement; he has also interviewed Chen Xitong, the then Party Secretary of Beijing during the 1989 democracy movement who was considered one of the main suppressors of the movement, and published a transcript of that interview in 2012, *Chen Xitong’s Personal Accounts*.

In April 2014, journalist Gao Yu was arrested by authorities for exposing a CCP document containing policies against media freedom and democracy. Yao was arrested in the same case and released on bail pending trial, but has never been fully freed. Yao was reportedly living in a nursing home but under close surveillance.

Yin Hongbiao

Yin Hongbiao (1951-), earned his bachelor’s degree from the Department of History of Jilin University, and a master's degree from the Department of International Politics of Peking University, where he majored in the relationship between the Communist International and the Chinese Revolution. He stayed at the university after graduation to teach, and obtained a doctoral degree. He later served as a professor at the School of International Studies of Peking University, and is now retired.

Yin's teaching and academic research areas include the history of the Chinese Communist Party and the history of the People's Republic of China, especially the history of the Cultural Revolution. His doctoral dissertation was on the Cultural Revolution, which was later expanded into a monograph Footprints of the Missing: Trends of Youth Thought During the Cultural Revolution. He has also published academic papers such as "The Main Factions of the Red Guard Movement" and "Social Contradictions in the Cultural Revolution."

Yu Luoke

Yu Luoke (1942-1970) was a worker and writer. His parents were both labeled Rightists during the 1957 Anti-Rightist Campaign, which made him a child of one of the "Five Black Categories," which formed what was essentially a permanent underclass in Mao's China (the others were landlords, rich farmers, counter-revolutionaries, and bad elements). For Yu, that meant he was not admitted to the university even though he scored well in the college entrance exams several times. Instead, he worked as a farmer, a substitute teacher and other part-time jobs before being assigned to the Beijing People's Machine Factory as an apprentice. After the Cultural Revolution began, in July 1966, Yu Luoke wrote an article entitled "The Theory of Origin" to refute the then-dominant theory that held that family origin determines the development of an individual. Yu argued that origin has very little influence on the performance of an individual, and criticized the persecution of young people from “bad” families, pointing out that this was a serious violation of human rights. The article was later published in January 1967 in the first issue of the Middle School Cultural Revolution Newspaper, which was founded by his brother Yu Luowen, and scholar Mou Zhijing. Yu Luoke later published several articles on the issue of origin in the newspaper under the pseudonym "Study Group on Family Origin." The newspaper was widely distributed and had a great impact. The article was later labeled "a great poisonous weed." On January 5, 1968, Yu Luoke was arrested, and on March 5, 1970, he was sentenced to death at the Workers' Stadium in Beijing, at the age of 27, and was immediately executed. On November 21, 1979, the Beijing Intermediate People's Court acquitted him.

To commemorate him, his friends and family, as well as Chinese and foreign scholars and human rights activists, erected a statue of him in 2009 at the Songzhuang Art Gallery in Tongzhou, Beijing, which was later dismantled after more and more people were visiting the statute to pay their respects with flowers. Other activities to commemorate him have also often been obstructed by the authorities.

Zhang Boli

Zhang Boli (born 1957), originally from Wangkui County, Heilongjiang Province, China, is a Christian pastor and a student leader of the 1989 Democracy Movement. He was once a student in the Writer’s Class at Peking University and played an important role in the 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement.

Zhang Boli attended primary and secondary school in Wangkui County, Heilongjiang Province. He later studied at Suihua Teachers College and Suzhou Railway Teachers College and worked as a journalist for the Railway Engineering Newspaper, where he wrote several reportorial literary works, such as The Success Story, Ha Mu Ha Mu, and The Road to the Sea. In 1988, he was admitted to Peking University’s Chinese Department Writer’s Class, where he studied under Cao Wenxuan and Qian Liqun. On April 15, 1989, he posted his first poem mourning Hu Yaobang, Longing for You: Rainy Night to Bid Farewell to Yaobang, on a bulletin board in the university’s triangle area. He, along with Wang Dan and others, organized the first student memorial march for Hu Yaobang at Peking University and participated in drafting the Seven Petition Clauses.

During the hunger strike at Tiananmen Square, Zhang Boli served as the deputy commander and the head of publicity for the Tiananmen student hunger strike group. One hour before the martial law declaration, he announced the end of the hunger strike and called for a sit-in protest. During the later stages of the Tiananmen protests, Zhang Boli served as the deputy commander of the temporary Tiananmen Command Center and the head of Tiananmen Democracy University. After the June 4th crackdown, he was listed as a wanted fugitive and escaped to the Sino-Soviet border in Heilongjiang Province, where he was sheltered by a local Christian. Later, he attempted to escape to the Soviet Union but was refused and sent back to China. He again hid in the wilderness of Heilongjiang, during which time his wife left him. Zhang Boli was the only June 4th wanted fugitive to successfully remain hidden within China for two years without being captured by the government.

In June 1991, Zhang Boli secretly escaped to Hong Kong and applied for political asylum at the U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong. His application was approved, and he was granted asylum in the United States. In July 1991, he was invited to Princeton University’s East Asian Department as a visiting scholar and became a researcher at the Princeton Chinese Studies Society. Due to kidney failure, he received treatment in the U.S. and later transferred to Taiwan’s Veterans General Hospital. During this period, he converted to Christianity and published his memoir <i>The Fugitive</i>, which has been translated into multiple languages.

In 1993, Zhang Boli participated in the overseas democracy movement conference in Washington, D.C., where he was elected as vice president of the Democratic China United Front and served as the editor-in-chief of China Spring magazine. In 1995, he began studying theology at Wheaton College, having decided to dedicate his life to the ministry. In 1997, he enrolled at Logos Evangelical Seminary in Los Angeles, where he earned a Master of Divinity degree and became a researcher at the China Evangelical Association, studying under Dr. Zhao Tian'en.

In 2001, Zhang Boli was ordained as a Christian pastor and in 2002, he founded and pastored the Harvest China Christian Church in the Washington, D.C., area. He later expanded the church to Singapore, New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Sydney. In 2018, he earned a Doctor of Ministry degree from Lincoln Christian University in the United States.

Zhang Boli also founded the China Evangelism Mission and the China Evangelical Seminary, which has produced over 300 graduates serving churches around the world. He is currently the senior pastor of the Harvest China Christian Church in the United States, the president of the North American China Evangelism Mission, and the dean of the China Evangelical Seminary in the U.S.

Zhang Chunyuan

Zhang Chunyuan (1932-1970), a native of Shangcai, Henan Province, was a writer, editor, and political prisoner.

Zhang grew up in an impoverished family. His mother died when he was 7 and he told friends that his stepmother mistreated him. He ran away from home at age 13 and worked as an apprentice car mechanic before joining the People’s Liberation Army in 1948 as a 16-year-old. He volunteered for the Korean war in 1950 and served as a car driver and technician in the Fourth Field Army’s 50th Army Logistics Department.

He went abroad to fight in the Korean War in 1950 and was wounded in 1953 on the battlefield while rescuing a vehicle. He was discharged in 1954, returned to China in 1955 and worked in the Department of Agriculture of Hubei Province.

In 1956, he was admitted to Lanzhou University. That began his disillusionment with how the Communists were running China. He thought a university would have a magnificent library but found that most books were under lock and key. Lanzhou University didn’t even possess a complete set of the Confucian classics—the basic texts used over the centuries by all literate people—let alone cutting-edge journals. Teaching was worse, with one lecturer for 100 students. When the Hundred Flowers Campaign began, Zhang criticized the lack of books and poor teaching.

For that, he was labeled a Rightist in 1958 and exiled to Tianshui, Gansu Province for re-education through labor. There, he and others students from Lanzhou University, including his girlfriend Tan Chanxue, Xiang Chengjian, Miao Qingjiu, and Gu Yan witnessed the Great Famine first-hand, including cannibalism.

Inspired by the poet Lin Zhao, they decided to publish a magazine. Zhang traveled to Suzhou to meet Lin, and convinced her to let them published “Seagull” and “A Day in the Life of Prometheus.”

Back in Tianshui, he and the other exiled students obtained a mimeograph machine, carved their own wax plates, and published the magazine Spark, which explored the reasons for the Great Famine and commented on current affairs.

Zhang was widely regarded by the students as one of the leaders of the magazine and also wrote several key articles. He was arrested on September 30, 1960, along with other students and dozens of local farmers who knew and supported them. In order to escape, Zhang refused to eat and was sent to a hospital for prisoners in July 1961. On August 10 he managed to escape but was arrested again on September 6 and sentenced to life imprisonment in January 1965 for “organizing a counter-revolutionary group”.

In March 1970, Zhang Chunyuan was again sentenced for engaging in counter-revolutionary activities by exchanging letters with another prisoner, Du Yinghua, a local party leader who had sympathized with the students. The two were sentenced during a mass rally at Qilihe Stadium and executed at Willow Gulley in Donggang Township on March 22.

For the three days before his execution, Zhang recounted his life story to a fellow prisoner named Wang Zhongyi and made him promise to find Tan Chanxue and tell her two sentences:

<i>First, I have a clear conscience toward the party, the country, and the people, and I’m sorry because I can’t accompany her to finish the road of life. Second, she must live well; the future is bright and boundless!</i>

Zhang was rehabilitated in 1981.

Zhang Dafa

Zhang Dafa, born in Gansu in 1946, is a writer and researcher of the Great Famine in China.

Zhang Wanshu

Zhang Wanshu (1938-), also known as Zhang Qinghai, is a journalist and writer. Born in Feixi County, Anhui Province, Zhang began his literary career in 1958. In 1964, he became a reporter for the Anhui branch of Xinhua News Agency, and later served as the director of news gathering and editing as well as vice president; in 1983, he was transferred to the Xinhua News Agency headquarters and served as deputy director of the Domestic News Department, and later as a director. In 1992, he became president and Editor-in-Chief of the Xinhua Publishing House. Zhang is also a member of the China Writers Association and was a deputy to the 6th National People's Congress.

Zhang is the author of several books of poetry and prose. His best-known poem, “Huangshan Pine,” was written in 1962, which praises the Chinese people during the Great Famine. The book <i>Introduction to the Classics of Red Poetry</i> published by Wuhan University Press called Zhang Wanshu an outstanding patriotic poet and his works are considered as “red” poems–in other words, pro-CCP.

However, as the director of the Domestic News Department of China's most authoritative news agency in 1989, Zhang witnessed the June Fourth massacre and directly handled first-hand accounts of Xinhua News Agency's correspondents throughout the country.

Around the 20th anniversary of June Fourth in 2009, Zhang’s book <i>The Big Bang of History: June Fourth Movement Record</i> was published in Hong Kong. It provides an authoritative chronology of events leading up to the bloodshed. The well-known independent historian Yang Jisheng, who was also a reporter for the Xinhua News Agency at the time, considered the authenticity of Zhang Wanshu's accounts to be beyond doubt. He said, “His accounts are true and reliable because he was informed and in the know. He was the director of the Domestic News Department at the time and knew what was going on at the upper levels, and he participated in the discussions of the Xinhua News Agency's leadership group every night.”

Zhang Zuhua

Zhang Zuhua (1955-), a native of Danyang, Jiangsu Province, is a constitutional scholar. Zhang graduated from the Political Science Department of Nanchong Normal College in 1982 with a bachelor's degree in philosophy, and has served as a Standing Committee member of the Communist Youth League Central Committee, and secretary of the Communist Youth League Committee of the Central State Organs. After the June 4th incident in 1989, he left government and in 1991-1992 studied the constitutional law of Western countries at the Graduate School of the China University of Political Science and Law. Since 1993, he worked as a researcher at independent civil society organizations including Sanhe Institute of Economics and Technology, and Jiuding Institute of Public Affairs. He also served as a visiting professor at the Department of Political Science and Law at Sichuan Normal University. Zhang was one of the drafters of Charter 08 and one of the editors-in-chief of Minzhu Zhongguo (Democratic China) magazine. He is mainly engaged in research on political modernization, the theory and practice of constitutional democracy, and political reform in China, and has published several books including *How to Build a Constitutional Democracy in China* and *The Rise of Civil Society in China*.

Zhao Dingxin

Zhao Dingxin (1953- ) is a sociologist. He received his undergraduate degree in biology from Fudan University in 1982, and later received his Master and Ph.D. degrees in Insect Ecology from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and McGill University in Canada, respectively. He then switched to sociology and received his Ph.D. in sociology from McGill University in 1995, and taught in the Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago from 1996 to 2021, where he served as assistant professor, associate professor, professor, and Max Palevsky professor emeritus. In 2012, Zhao joined the School of Public Administration at Zhejiang University, where he served as visiting professor, professor, Dean of the Department of Sociology, and Director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Humanities and Social Sciences. In March 2024, Zhao resigned from all positions related to the Department of Sociology.

Zhao Dingxin's research interests include political sociology, social movements, and historical sociology, and he is the author of *Social and Political Movements* and *The Power of Tiananmen: State - Society Relations and the 1989 Beijing Student Movement*.