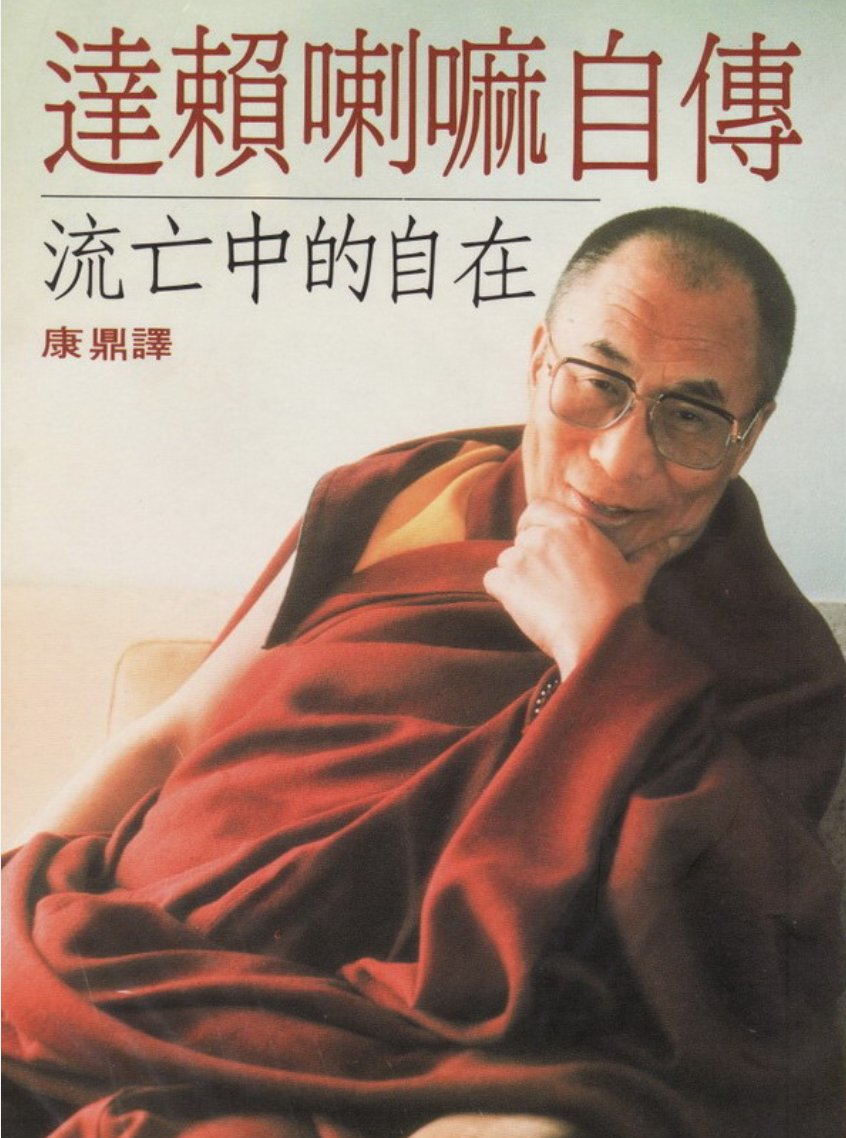

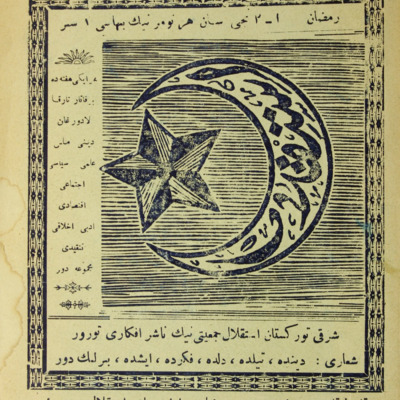

Istiqlal mejmu’esi/The Independence

“Istiqlal” mejmu’esi 1930-yillarning bashliridiki Sherqiy Türkistan milliy inqilabi we uning netijiside qurulghan Sherqiy Türkistan Islam Jumhuriyiti heqqide birinchi qol tarixiy menbe bergüchi siyasiy, ijtima’iy, iqtisadiy, diniy, edebiy we tenqidiy mejmu’edur.

20-esirning aldinqi yérimidiki Sherqiy Türkistanning siyasiy we ijtima’iy tarixi tetqiqatida Uyghurlarni asas qilghan yerlik xelqlerning aghzaki tarix matériyalliri hemde yazma menbelirige étibar bérilmey keldi. Uyghurlarni asas qilghan yerlik milletler 1930-we1940-yillardiki Sherqiy Türkistanning siyasiy tarixida asasliq rol alghuchi ijtima’iy topluq hésablansimu, emma meyli kommunist Xitay istilasidin kéyinki Xitay hökümet tarixshunasliqida bolsun yaki xelq’aradiki Ottura Asiya tetqiqatida bolsun, ularning öz til-yéziqidiki tarixiy menbeler hemde ularning éytimidiki yerlik tarixchiliq en’enisi izchil halda nezerdin saqit qilinip keldi. Téximu éniqraq qilip éytqanda, Uyghurlarning hazirqi zaman tarixi ularning öz éytimida emes, belki Xitay hökümet tarixshunasliqining ramka ichidiki éytimida yézilip keldi; Ularning öz béshidin ötküzgen tarixiy kechürmishliri ularning öz tili, öz yéziqi we öz hékayiliridiki éytimlarda emes, belki bashqilarning tili, yéziqi we hékayiliridiki wastiliq bayanlarda éytilip keldi. Shundaq, ularning özlirini ipade qilishigha imkaniyet bérilmidi, ular peqet bashqilar teripidin ipade qilinishqa mejbur boldi.

“Istiqlal” mejmu’esi 1930-yillardiki Sherqiy Türkistan milliy inqilabi tarixidiki del mushu boshluqni toldurghuchi Uyghur til-yéziqidiki yigane menbelerning biridur. Eslide mezkur mejmu’eni her ikki heptide bir qétim neshir qilip tarqitish pilanlan’ghan bolsimu, emma 1933-1934-yillardiki Rayonning murekkep we turaqsiz siyasiy weziyiti seweblik, peqetla 1-2 qoshma sani neshir qilinipla toxtap qalghan. Bügünki künde mezkur mejmu’ening esli nusxasini Xitaydiki, jümlidin Shinjang Uyghur Aptonom Rayonidiki herqandaq bir arxip yaki kutupxanidin tapqili hem körgili bolmaydu. “Istiqlal” mejmu’esining birqanche dane esli nusxasi nöwette Seudi Erebistanidiki Türkistan Kutupxanisida, Shiwétsiyediki Lund Uniwérsiteti Kutupxanisi Yarring Yighmisi (Gunnar Jarring Collection)da, Shiwétsiye dölet arxipi (Riksarkivet) da we Istanbuldiki Shiwétsiye Tetqiqat Inistituti (Swedish Research Inistitute) ning kutupxanisida saqlanmaqta.

“Istiqlal” mejmue’si 1933-yilining ikkinchi yérimida Qeshqerde qurulghan Sherqiy Türkistan Istiqlal Jem’iyitining neshir epkari süpitide neshir qilin’ghan. 1931-yili Qomuldin bashlan’ghan Sherqiy Türkistan milliy inqilabi 1933-yilining bashlirigha kelgende jenubqa kéngiyip, aldi bilen Xoten wilayiti yerlik qozghilangchilarning qoligha ötken we Xoten Islam Hökümiti jakarlan’ghan. Shu yili 5-aylarda Qeshqer wilayitimu yerlik qozghilangchilarning qoligha ötüp, Qeshqerde birlikke kelgen musteqil Sherqiy Türkistan Jumhuriyiti qurushning jiddiy teyyarliqi élip bérilghan. 1933-yili 8-ayda Qeshqerde bir qisim yerlik inqilabchi serxillar bash qoshup, aldi bilen Sherqiy Türkistan Istiqlal Jem’iyiti qurghan we musteqil Sherqiy Türkistan Jumhuriyiti qurushning teyyarliqigha jiddiy kirishken. “Istqiqlal” mejmu’esi mezkur jem’iyetning neshir-epkari süpitide qurulghusi Sherqiy Türkistan Islam Jumhuriyiti üchün siyasiy we nezeriyiwiy asas tiklesh meqsitide neshir qilin’ghan.

“Istiqlal” mejmu’esining 1933-yilliq tunji sani (1-2-qoshma sani)da mezkur mejmu’ening meqset-nishani, Sherqiy Türkistan Istiqlal Jem’iyitining nizamnamisi, Qeshqerde Sherqiy Türkistan Islam Jumhuriyitining qurulushi we hökümet bayannamisi, hökümet teshkili we kabént ezaliri, Sherqiy Türkistan Islam Jumhuriyitining asasiy qanuni, Sherqiy Türkistan milliy inqilabining qisqiche tarixi, Sherqiy Türkistan xelqige qilinghan chaqiriq, Chet’ellerdiki Türk-musulman qérindashlargha muraji’et, Sherqiy Türkistan dölitining yéngi pul-mu’amilisi qatarliq höjjet xaraktérliq muhim matériyallar bérilgen. Mejmu’ening kéyinki bölikide Sherqiy Türkistandiki eng yéngi weziyet we milliy inqilab xewerliri hemde Qeshqer ehwali tonushturulghan. Alahide tekitleshke tégishlik yéri shuki, mejmu’ening axiriqi sehipiliride Sherqiy Türkistan Edebiyatigha béghishlan’ghan mexsus maqalilar, she’irlar, chaqiriqlar, mektep balilirining naxsha tékistliri we Sherqiy Türkistan marshi bérilgen.

Mezkur mejmu’ediki höjjet xaraktérliq matériyallar 1933-yilidiki Sherqiy Türkistan Islam Jumhuriyiti tarixini tetqiq qilishta birinchi qol muhim menbe hésablinidu. Bu mejmu’ege bésilghan Sherqiy Türkistan Islam Jumhuriyitining Asasi Qanuni shu mezgildiki musulmanlar dunyasida küchlük tesir peyda qilghan. Eyni waqitta Yawropada siyasiy pa’aliyet élip bériwatqan Türkistan muhajirliri Qeshqerde neshir qilin’ghan “Istiqlal” mejmu’esidiki bir qisim maqale we höjjetlerni tashqiy dunyagha tonushturghan. “Istiqlal” mejmu’esining tunji sanigha bésilghan Sherqiy Türkistan Islam Jumhuriyitining Asasiy Qanunining toluq tékisti Fransiye paytexti Parizhda neshir qiliniwatqan “Yash Türkistan” mejmu’esining 1934-yilliq 3 sanigha uda ulap bésilghan.

“Istiqlal” mejmu’esining ich muqawisigha “bu mejmu’ening shu’ari dinda, tilda, dilda, pikirde we ishta birlik” dep yézilghan. Bu shu’ar 19-esirning axiriqi charikide Rusiye musulmanliri arisida bashlan’ghan jeditizm herikitining bayraqdari Ismail Gaspirinski (1851-1914) teripidin otturigha qoyulghan “tilda, pikirde we ishta birlik” dégen meshhur chaqiriqtin élin’ghan.

“Istiqlal” mejmu’esi Hijriye 1352-yilining Ramizan éyida, Miladiye 1933-yilining 11-12-ay mezgilide Qeshqerde neshir qilinip tarqitilghan. Mezkur mejmu’ening bash muherriri Muhemmed Emin Sufizade bolup, u 20-esirning bashlirida Tashkent, Buxara, Istanbul we Misirda oqughan. 1920-yillarda Rusiye Türkistanida Bolshéwiklar hakimiyitige qarshi qurbashilar (basmichilar) herikitige qatnashqan. 1930-yillarning bashliridiki Sherqiy Türkistan milliy inqilabi mezgilide neshriyatchiliq we teshwiqat ishlirida aktip rol oynighan. Qeshqer we Aqsu qatarliq jaylarda oqutquchi bolup, zamaniwiy milliy mekteplerni rawajlandurushta hesse qoshqan. 1937-yili Sherqiy Türkistan milliy inqilabi meghlub bolghandin kéyin qolgha élinip, Ürümchide militarist Shéng Shisey türmiside öltürülgen.

“Istiqlal” mejmu’esining tili klassik Türki-Uyghur (Chaghatay) tilidin hazirqi zaman Uyghur tiligha ötüsh mezgilidiki ötkünchi dewrge mensup bolup, uningdiki maqale-eserler til, yéziq, imla we ipadilesh jehettin pütkül Türki tilliq xelqler chüshineyleydighan ortaq edebiy tilda yézilghan. Bu mejmu’ediki maqale-eserler hazirgha qeder Xitay, In’giliz yaki bashqa tillargha terjime qilinmighan.

The irregular periodical <i>Istiqlal (The Independence)</i> is a firsthand historical source concerning the national independence movement that erupted in East Turkestan in the early 1930s and its direct outcome — the establishment of the East Turkestan Islamic Republic (ETIR) on November 12, 1933. It is a valuable collection of documents that provides critical, self-reflective content about the political, social, economic, religious, and cultural environment of East Turkestan during that era.

In the study of China's frontier history during the first half of the 20th century, particularly in the field of modern political and social history of Xinjiang, oral histories and written records of local people, primarily the Uyghurs, have long been overlooked. Despite the fact that Uyghurs and other indigenous people played a central role as the main social actors in Xinjiang's political history during the 1930s and 1940s, both official Chinese historiography after the rule of the Chinese Communist Party and international scholarship on Xinjiang have consistently ignored historical documents in the languages of Xinjiang's indigenous peoples and their native historiographical traditions. To be precise, modern Uyghur history is not narrated by the Uyghurs themselves but is framed within China's official historical narrative. Their historical experiences are not expressed through their own language, script, and stories but are instead conveyed through the language, script, and narratives of others.

<i>The Independence</i> anthology is a rare historical document in the Uyghur language that fills this gap. According to the original plan of its publishers, Independence was intended to be issued biweekly. However, due to the complex and turbulent political situation in southern Xinjiang during 1933-1934, only the combined first and second issues were published before its discontinuation. Today, the original copies cannot be found in any archives or libraries within China, including the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. A small number of surviving original copies are held in the private library of Rahmetulla Turkistani, a Saudi Arabian scholar of Uyghur descent, the Gunnar Jarring Collection at Lund University Library in Sweden, the National Archives of Sweden (Riksarkivet), and the library of the Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul, Turkey.

The PDF version offered here came from the website of <a href="https://www.uyghurkitap.com/">"UyghurKitap" (UyghurBook)</a>. The founders of UyghurKitab website scanned the book and converted it into PDF with the permission of the Library of Rahmetulla Turkistani. CUA got permission from the UyghurKitab to publish it on our website.

Published in Kashgar in the second half of 1933 as the official publication of the East Turkestan Independence Association, the anthology emerged during a pivotal time. The East Turkestan national independence movement, which began in Qomul (Hami in Chinese) in 1931, had spread to various oases around the Tarim Basin by early 1933. The main southern East Turkestan oasis cities such as Hotan, Kashgar, and Aksu were successively brought under the control of local insurgent populations. Various rebel forces began preparations to establish a unified East Turkestan Republic. In August of that year, local rebel elites formed the East Turkestan Independence Association to actively prepare for the founding of the Islamic Republic. The Independence anthology served as the theoretical mouthpiece of this association, aiming to awaken the populace and lay the political and ideological foundation for the forthcoming Islamic Republic of East Turkestan.

The first combined issue of <i>The Independence</i> anthology (Issues 1-2, 1933) includes the following core content:

- The editorial mission and the charter of the East Turkestan Independence Association (ETIA)

- The declaration of the East Turkestan Islamic Republic (ETIR) established in Kashgar

- The composition of the government of the East Turkestan Islamic Republic and the list of cabinet members

- The full text of the Constitution of the East Turkestan Islamic Republic

- A brief history of the East Turkestan national independence movement

- A Letter to the People of East Turkistan and A Letter to Overseas Turkic Muslim Brothers

- An announcement regarding the issuance of new currency by the East Turkestan Islamic Republic

In the later sections, updates on the latest developments in East Turkistan, trends in the independence movement, and reports from the Kashgar region were published. Notably, the final section of the publication featured a dedicated East Turkestan literature column, including essays, poetry, manifestos, ethnic folk songs, and the lyrics to the East Turkestan March.

The documents published in the inaugural issue are indispensable historical materials for a comprehensive study of the East Turkestan Islamic Republic (1933-1934), which holds special significance in 20th-century Uyghur political history. The Constitution of the East Turkestan Islamic Republic, published in the anthology, had a profound impact on the Islamic world at the time. Political activists from Russian Turkestan (or Soviet Central Asia), who were in exile in Europe, introduced parts of the publication and its documents to the international community, including the full text of the Constitution of the East Turkestan Islamic Republic. This was subsequently reprinted over three consecutive issues in 1934 in the Paris-based magazine <i>Yash Türkistan (Young Turkistan)</i>.

The cover of the anthology bears the motto: "Unity in Religion, Language, Heart, Thought, and Action." This slogan is derived from the famous 19th-century initiative "Unity in Language, Thought, and Action," proposed and widely disseminated by Ismail Gasprinsky (1851-1914), a leader of the Russian Tatar Jaditism Movement (Muslim reform movement), in his periodical <i>Terjuman</i>.

<i>The Independence</i> anthology was published in Kashgar during the month of Ramadan in the Islamic year 1352 (November-December 1933 AD). Its editor-in-chief, Muhammed Emin Sufizade, had studied in Tashkent and Bukhara (present-day Uzbekistan), Istanbul (Turkey), and Cairo (Egypt) in the early 20th century. In the 1920s, he participated in the Basmachi movement against Bolshevik rule in Western Turkestan (Russian Central Asia). In the early 1930s, he dedicated himself to propaganda and publishing efforts for the East Turkestan independence movement, founding modern national education schools in Kashgar and Aksu. Following the failure of the East Turkestan independence movement in 1937, he was arrested by the warlord Sheng Shicai and executed in a prison in Urumqi.

The language of the publication largely reflects the transitional form of classical Turkic Chagatay literature into modern Uyghur, using a common written language comprehensible to readers across the Turkic language world. More specifically, the vocabulary, orthography, grammatical structure, and style of expression in the anthology embody the characteristics of early 20th-century Uyghur written language. It should be noted that the content of this anthology has not yet been translated into Chinese, English, or other languages.

The Falun Gong Phenomenon

This book is a collection of several long articles and commentaries by Hu Ping on Falun Gong and the persecution and repression against Falun Gong practitioners. From an independent perspective, this book responds to a series of unfair criticisms and stigmatization of Falun Gong by the Chinese authorities and the public, calling on society to fight for the basic rights of Falun Gong practitioners who have been persecuted.

Songs from Maidichong

This film was shot in a village called Maidichong in the mountains of Yunnan Province. The village is inhabited by a community of Miao people who are Christians. More than 100 years ago, the British missionary, Samuel Pollard, came to this village, invented the Miao script, and brought faith, education, and medical care to the Miao people. This film tells this history and how their journey of faith was brutally suppressed during the Cultural Revolution. It also presents the challenges they face today.

Pastor Wang Yi's Anthology: Carrying the Cross - A History of Chinese Family Churches

Wang Yi, of Chengdu, Sichuan Province, is a well-known Chinese intellectual who later became a pastor. The Early Rain Reformed Church that he led was one of the most famous unregistered churches in China. The church occupied the floor of an office building in Chengdu and had its own bookstore, seminary, and pre-school. It regularly had services of hundreds of people. Later, the church had internal conflicts, while at the same time Wang became more outspoken in his criticism of the government. In 2018, he criticized Xi Jinping for abolishing term limits and allowing himself to become ruler of China for life. Pastor Wang was sentenced to nine years in prison in 2019.

This book is based on the recordings of Pastor Wang's classes at Early Rain in 2018. The first five chapters were reviewed by Pastor Wang himself, but he was arrested before he could complete the review of the last five chapters. The essays cover key issues that concerned Wang, including the role of the church in China as a city on the hill, the role of the Reform church in China, and the history of unregistered churches in China.

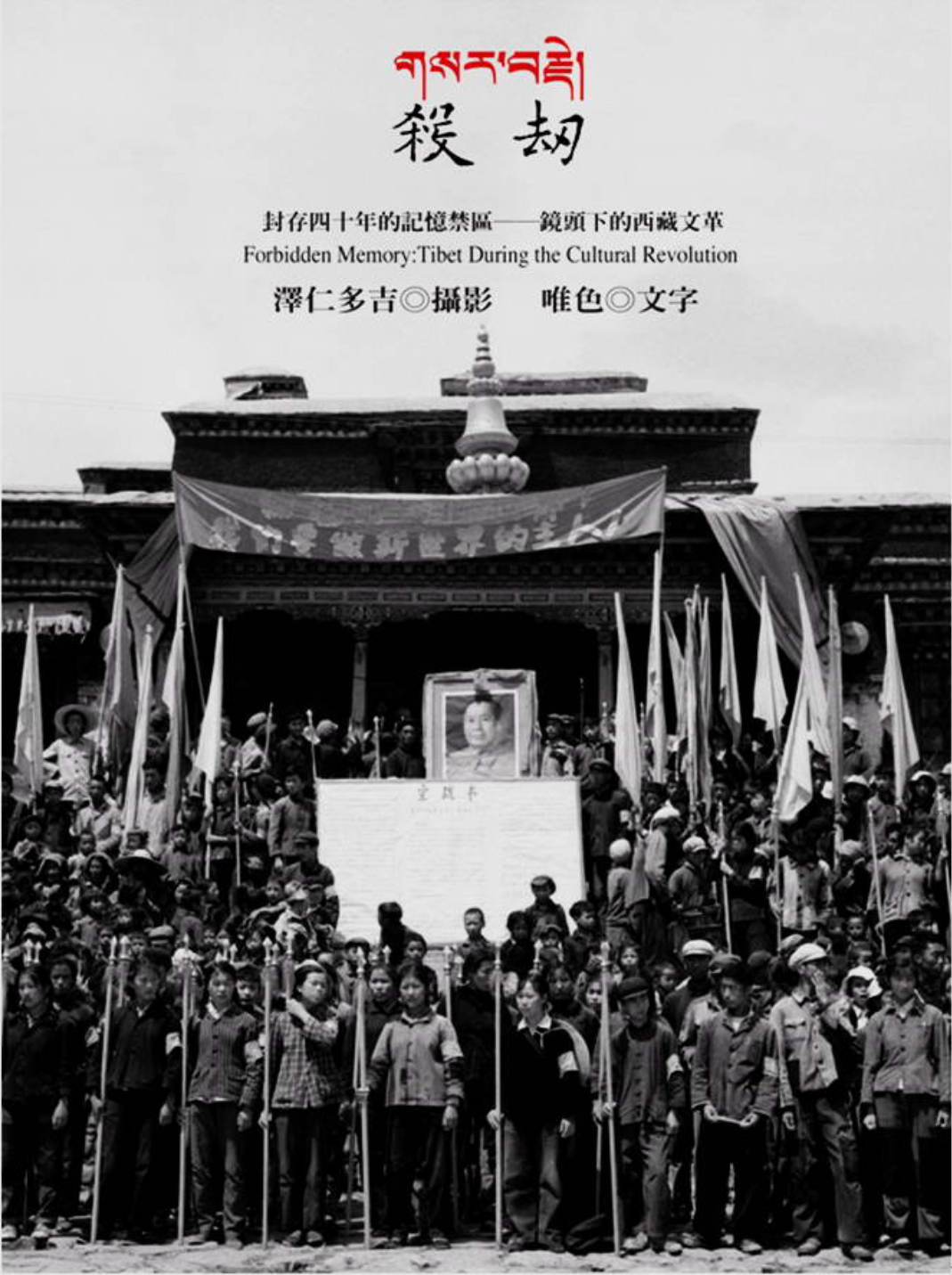

Killing and Hijacking: Tibet's Cultural Revolution Through the Lens

In 1966, when the flames of the Cultural Revolution began to spread, writer Tsering Woeser (唯色) was born in the General Hospital of the Tibetan Military Region. Her father was an officer in the People's Liberation Army (PLA) in Tibet at the time, and an avid photographer. Through his camera lens, the officer recorded the most comprehensive collection of images of the Cultural Revolution in Tibet to date. Tsering Woeser, on the other hand, restores and records the story behind the camera lens: It was an attempt to fight against oppression and preserve the true history of Tibet during the Cultural Revolution.

Gu Zhun and His Times

This book is about Gu Zhun, a Chinese economist, historian and philosopher. Gu Zhun was the first person to put forward the theory of China's socialist market economy, which became a key concept in the Reform era, helping to justify the use of markets in a socialist system. He also devoted himself to the study of politics, history and philosophy, translating several foreign classic works on economics and democracy and writing a large number of articles. Due to his independent thinking and dissent, he suffered repeated political persecution, including during the Anti-Rightist Campaign and the Cultural Revolution (for more information on Gu Zhun, see his biographical entry). As he personally experienced the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Great Famine, and the Cultural Revolution, his diary is also considered a valuable source of information on these historical events. By documenting and analyzing his life, thoughts, and the eras in which he lived, Wang's book shows how Gu Zhun persisted in his "pursuit and search for the freedom and equal rights that are inherent to all human beings " (author's preface) in an era when independent thinking was suppressed. This book was published in 2015 by the Great Mountain Culture Publishing House in Hong Kong.

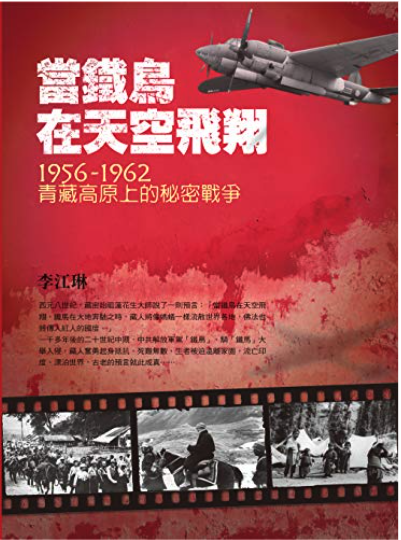

When the Iron Bird Flies: China's Secret War in Tibet

Around the eighth century A.D., the founder of Tibetan Buddhism, Guru Rinpoche, prophesied, "When the iron bird flies in the sky and the iron horse runs on the earth, the Tibetans will be dispersed all over the world like ants, and the Buddha's Dharma will be spread into the land of the red people." More than 1,000 years later, in the middle of the 20th century, the Chinese Communist Party drove the "iron bird" across the sky and rode the "iron horse" across the plateau. The Tibetans courageously rose up to resist resulting in with countless deaths countless deaths. Those who survived were forced to leave their homeland and live in exile in India, drifting around the world. Thus, the prophecy came true. From a military point of view, the Tibetan war in Tibet was a victory, but it received only minimal publicity. The official version of the Party's history is either vague or evasive about the bloody massacre during the entry into Tibet, attempting to cover it up by "suppressing armed rebellion" and "purging counter-revolutionaries". More than sixty years later, this war has yet to be demystified. Li Jianglin, an independent scholar, was moved by the tragedy of the war and the plight of the Tibetans, and endeavored to restore the historical facts. Since 2004, she has devoted herself to research, visiting hundreds of Tibetan elders, searching for tens of thousands of historical materials, collecting military archives, and comparing them with the official published materials of the Communist Party of China, in order to present memories of past, little by little.

Sky Burial: The Fate of Tibet

In this book, author Wang Lixiong presents his arguments with a great deal of personal experience and field work. The book covers the history of the Tibetan issue, the current situation, and various aspects. The book was first published by Mirror Books in Hong Kong in 1998, and an updated edition was released in 2009.

Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959

Traveling Chinese history scholar Li Jianglin began working on the Tibet issue in 2004. She has traveled to India every year in search of Tibetan refugees, visited 14 Tibetan refugee settlements in India and Nepal, contacted more than 200 exiled Tibetans from the three regions of Tibet, and personally interviewed the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, the seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile, in 2008. In 2010, Li Jianglin completed her book <i>Lhasa 1959!</i> by drawing on interviews, information searches, and rare historical photographs provided by the Tibetan government in exile, in the hope of reconstructing the little-known history of the Dalai Lama's departure from Tibet in 1959. The book was published by Taiwan's Lianjing Publishing House in 2010 and reprinted in 2016.

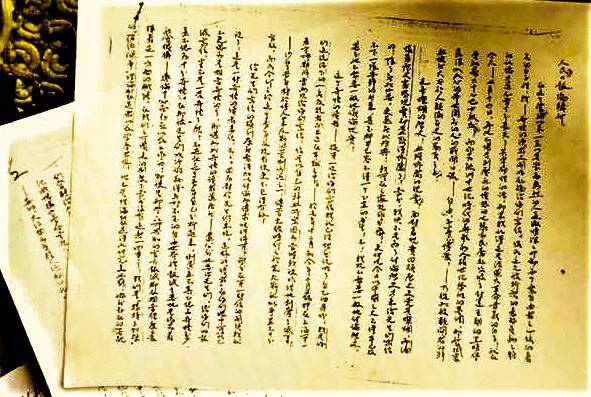

Lin Zhao: A Letter to the Editorial Board of People's Daily

This is one of the most significant essays written by Lin Zhao, the pen name of the Christian intellectual Peng Lingzhao, who was born on January 23, 1932 in Suzhou.

In 1947, she attended a Methodist girls school and was baptized. Soon after, however, she joined the underground Communist Party and began writing critiques of the Kuomintang-led government under the pen name Lin Zhao. Before the Communist takeover in 1949, Lin Zhao ran away from home to attend a journalism school run by the party. During this time she joined party campaigns to eradicate the landholding gentry that ran local society.

Lin Zhao was admitted to the Chinese Department of Peking University in 1954. It was there that she broke with Communism and gradually rediscovered her Christian faith. She was classified as a rightist in 1957 for speaking up for other students. During this time, she met Zhang Chunyuan, one of the founders of the magazine "Spark," which the China Unofficial Archives also holds. She contributed two epic poems to the magazine. The magazine was shut down in 1960 and people affiliated with it were detained, including Lin.

She was released on medical parole in early 1962 due to tuberculosis, but was arrested and imprisoned again in December of the same year. She was detained in Shanghai No. 1 Detention Center and Tilanqiao Prison. When she was denied a pen and paper, she sometimes used a sharpened straw or chopstick to prick her finger and write in blood.

While in prison, she wrote a large number of texts, including the 140,000-word essay to <i>People’s Daily</i> that we feature here. This essay is the fullest expression of Lin’s political beliefs. She wrote it in 1965, dating it July 14 because it was the date of the storming of the Bastille in the French Revolution. It took Lin five months to finish the letter, which ran to 137 pages. She wrote the essay in ink, but stamped it repeatedly with a seal bearing the character “zhao” that she inked in her own blood.

The letter has not (yet) been translated into English so a few salient points are worth mentioning.

As Lin’s biographer, the Duke University professor Lian Xi wrote in his biography of Lin (<i>Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao’s China</i>, Basic Books, 2018):

“Lin Zhao challenged the theory of a continuous ‘class struggle,’ which the Communists saw as intrinsic to human history and from which there was no escape. Since the 1920s, the CCP had looked upon this theory as an immutable truth and had used it to justify the so-called dictatorship of the proletariat after 1949….”

Lin Zhao scoffed at this. ‘I do not ever believe that, in such a vast living space that God has prepared for us, there is any need for humanity to engage in a life-and-death struggle!’ The CCP dictatorship was but a modern form of ‘tyranny and slavery,’ she wrote in her letter to the party’s propagandists.

“'As long as there are people who are still enslaved, not only are the enslaved not free, those who enslave others are likewise not free!,' she wrote. Those seeking to end Communist rule in China must likewise not ‘debase the goal of our struggle into a desire to become a different kind of slave owner.' ‘The lofty overall goal of our battle dictates that we cannot simply set our eyes on political power—the goal must not and cannot be a simple transfer of political power!’"

“The end was ‘political democratization… to make sure that there will never be another emperor in China!"

Professor Lian continues: “Lin Zhao wrestled with the moral question of whether violence was a justified means to that end. Her Christian faith had hardened her for the fight. At the same time, it also tempered her opposition. She acknowledged the occasional ‘sparks of humanity’ even in those who were at the ‘most savage center’ of Chinese communism. As strenuously as she argued against her imprisonment, against Mao’s dictatorship, and for a free society, she was unable to sanction violence in that struggle. ‘As a Christian, one devoted to freedom and fighting under the Cross, I believe that killing Communists is not the best way to oppose or eliminate communism.’ She admitted that, had she not ‘embraced a bit of Christ’s spirit,’ she would have had every reason to pledge ‘bloody revenge against the Chinese Communist Party.’”

The same year that the letter was finished, Lin Zhao was sentenced to 20 years for counterrevolutionary crimes. On April 29, 1968, the sentence was changed to death and she was executed on the same day. She was 36 years old.